Biography

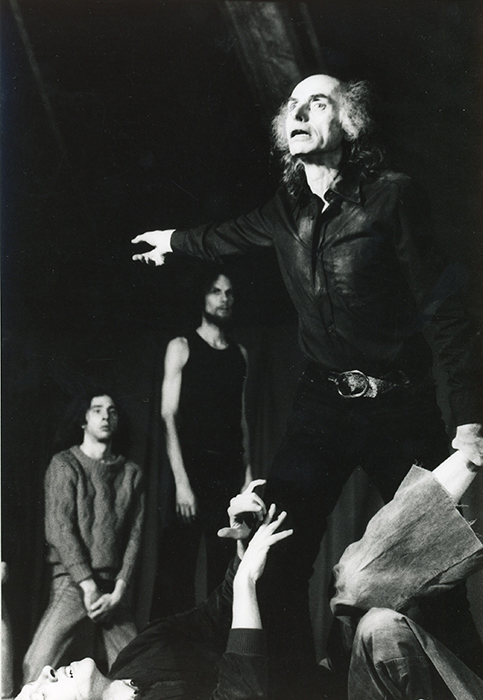

Julian Beck was born in New York City on May 31st, 1925. His talent as an actor, writer, set designer and theatre director was already evident in the nineteen-thirties while he was a pupil at the Horace Man High School, with classmates such as future beat generation writer Jack Kerouac and Kenneth Kock who would later be awarded the Pulizter Prize for literature.

In 1943, he abandoned his studies at Yale University, saying that he could “no longer serve what he did not believe in”, meaning the way of thinking imposed by the academic world, so he returned to New York City, intending to dedicate himself to painting and writing. That was the year he met his life partner, Judith Malina. They founded the Living Theatre together in 1947, and for the next forty years staged experimental plays which left a profound and lasting mark on twentieth-century Western culture.

As a painter, Julian belonged to the New York school of abstract expressionism, exhibiting at Peggy Guggenheim’s “Art of This Century” gallery, among others alongside Jackson Pollock and other prominent figures involved in the movement from 1945-1958. He went on to develop his artistic talent principally in the field of set design, for which he gained international recognition.

The three premises occupied by the Living Theatre in New York from 1951 to 1963 were home to twenty-nine shows, some of which were directed by Julian, who designed all the sets, lighting and costumes, and he appeared on stage in most of them. With the enthusiastic support of prominent figures from the world of entertainment, such as John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Jean Cocteau and Paul Goodman, the Living Theatre was a place of extreme freedom, which made it perfect for artists, poets, writers and activists to meet and share their work.

From 1959 onwards, the Living Theatre, in its third home on New York’s 14th Street, stood out as the meeting place for the avant-garde, including beat generation poets, action painters, underground film makers and contemporary composers as well as cool jazz musicians.

A pacifist anarchist, Julian Beck took part in civil disobedience protests leading to numerous arrests. From 1960 to 1963, he promoted the General Strike for Peace with Judith Malina. This event, repeated on two separate occasions, resulted in massive public demonstrations not only in New York and San Francisco, but also around Europe, such as the demonstration organised by Nobel Peace Prize winner, Bertrand Russell.

The Strikes for Peace, organised from the premises of the Living Theatre, actively involved the majority of its members in the preparation of events that culminated in the 1963 opening of The Brig, a performance by former marine, Kenneth H. Brown. Denouncing the mistreatment of US Marines by other US Marines in military reformatories, the play led to an investigation by Congress and aroused much controversy, reaching the pages of the “New York Times” and “Life Magazine”.

Around this time, the Internal Revenue Service closed the Living Theatre down on the pretext of tax arrears, despite the fact that the Living Theatre was a not-for-profit company and therefore exempt from taxes. Julian and Judith ended up in court, ready to defend themselves in person, a gesture in keeping with the movement’s position on civil rights at the time; they were sentenced to 60 and 30 days’ in prison respectively, to be served at the New York Federal prison. This provided the occasion for the entire company to choose the path of voluntary exile.

After two European tours in 1961 and 1962, the company was already known internationally as an expressive example of the new American theatre, the off-Broadway movement. It had won a significant number of awards and had attracted much praise. When he returned to Europe in 1964, he was warmly welcomed by the public in several countries, where his counter-culture and the example he set were much appreciated. Julian and Judith were already well known for their bold statements on both art and politics, underlined by the more daring aspects of their productions, which became subjects of debate, but were also highly acclaimed.

Julian and Judith had shared a dream since the nineteen-fifties, namely a company that would endeavour to do everything necessary to build up a repertoire of performances, doing away, in true anarchic spirit, with both producer and director. This was a dream that would only come true during their European exile. It was during their travels from country to country between 1964 and 1968 that the company developed its tribal identity. They became nomads: a group of artists open to the public, seeking to elicit a spark of political awareness.

The first, and varied, works created by its members, Mysteries and Smaller Pieces (1964), Frankenstein (1965) and Paradise Now (1968), conferred upon the Living Theatre an important role as innovators in contemporary western theatre.

Beck’s poetry played an important part in the formation of these collective creations. His first book of poems – Songs of the Revolution – came out in New York in 1963. New editions of this series of poems appeared with the same title, and Julian would keep on writing them for the rest of his life in English, French, German and Dutch. He would continue to do so throughout the sixties, seventies and eighties. With Judith Malina, he wrote Il lavoro del Living Theatre, and together with her and Aldo Restagno We, The Living Theatre, while with Jean-Jacques Lebel he authored Entretiens avec le Living Theatre. Julian appeared in front of the camera in a number of films in the sixties, such as Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Edipo Re and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Agonia.

After a year of experimental street theatre in Brazil in 1970-1971, leading to his arrest and the expulsion of the Living Theatre by the military regime, Julian returned to the US and published The Life of the Theatre, recently republished by Limelight Editions. It has also been published in Italian, Spanish, French, and Greek editions.

Working in close contact with workers, students, artists and activists, the Living Theatre continued its activities in the United States until 1975 when it returned to Europe at the invitation of the Venice Biennale. Performing in the street and in unconventional environments, and working with theatre festivals and alternative cultural circles, the Living Theatre once more became an itinerant group, touring the whole of Western and Eastern Europe until 1983.

Its activities, all bearing the hallmark of political commitment, resulted in the production of more than 30 shows in different styles and of varying length. Seven Meditations on Political Sado-Masochism (1972), Strike Support Oratorium (1973), The Money Tower (1975) and Six Public Acts to Transform Violence into Concord (1975) were milestones in this sense. Julian Beck wrote two plays, Prometheus at the Winter Palace (1978) and The Archaeology of Sleep (1983), all of which were staged in New York in 1984.

Diagnosed with cancer in 1983, he spent the last two and a half years before his death on September 14th, 1985, acting in films like Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club (1984) and Brian Gibson’s Poltergeist II – The Other Side (1985). In 1985, in addition to appearing in television series such as Miami Vice and All My Children, and in Nam June Paike’s art videos, Julian trod the boards for the last time in Beckett’s monodrama, That Time at La Mama in New York and in Frankfurt, Germany. (He was also meant to appear at the Venice Biennale, that September).

His book of poems, Daily Light, Daily Speech, Daily Life, came out in a bilingual edition in Italy that year. Julian left a manuscript on the metaphysics of the theatre, titled Theandric, for which he had been awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship (the book was published in London by Harwood Academic Publishers in 1929), as well as The Last Songs of the Revolution, and a large number of writings that go to form what he called his Workbooks. Many of his paintings were shown at the Venice Biennale in an exhibition curated by Arturo Schwartz in 1986. A retrospective of his paintings was also held by Dore Ashton at the Cooper Union in 1986, followed by an exhibition of his pastel drawings at the Bleeker Street Gallery, both in New York and Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1993.

After receiving numerous awards for his accomplishments in the theatre, including the Grand Prix of the Theatre of Nations, the New York Newspaper Guild’s Page One Award, the Brandois University Creative Arts Citation and half a dozen Obies, Julian Beck left the cultural scene as an artist of extraordinary achievement and exemplary integrity, and the work he produced in the course of his lifetime has inspired generations of viewers and readers around the world.

By Ilion Troy and Hanon Reznikov

Julian Beck, the Painter

Julian Beck, the Painter. There are many doubts in need of clarification: was he really a genius or was he a gifted dabbler? Why did he really give up? As in poetry and the theatrical arts of directing, acting, and set design, Beck the painter was self taught. He had an insatiable need to express himself. Nothing satisfied him. ‘We now have to face different choices and address confusion, we are confused…. Once more, the difficulty is my want-to-do-it-all personality’, he wrote in 1962. The drive to search pushes him (paraphrasing Picasso he writes, Je ne trouve pas, je cherche).

While it is undeniable that Beck originally embraced the form known by the label of Action Painting, it would be a mistake to consider him an abstract expressionist, because, like many artists of his day and many future generations, Beck is first and foremost a product of Surrealism and Dadaism. Even at his most abstract, Beck is a romantic, a naturalist, and for this reason he cites William Bazoties, whose work is certainly closer to his than Pollock’s. Bazoties says in his diaries, ‘Every time I paint something there’s always an image; sometimes I know what it is, sometimes I don’t’.

Beck paints the spirituality of nature, the flowers of the mind, the rocks of the metaphysical landscape, shining like crystals. But over his dazzling insights there always hangs the sword of an inflexible rationalism, to the point that we cannot avoid speaking of Julian Beck the Scientist and Philosopher. In ‘The Life of the Theatre’ (1970-72), he quotes Judith Malina once again: ‘You can’t trust inspiration. We cannot build a strategy for creation based on something so uncertain. On September 1st, 1962, he wrote in his diary: ‘[I don’t have the money to buy artistic supplies to paint] … but I made some preliminary drawings, I did up to 28 in one day’. But he always had a strong sense of self-criticism; in the same diary, a fortnight later we read: ‘Tonight I destroyed a lot of my paintings and drawings, over 50’. Between 1943 and 1958, official dates that circumscribe his career as a painter, Julian Beck’s personal catalogue shows that he produced precisely 1,505 paintings and drawings on paper. Much has been lost, and what remains today is just the tip of the iceberg. Chance intervened where Beck himself did not, in the form of a couple of disastrous floodings in the basements of kind friends who had stored his work over the years during his repeated stays in Europe, North Africa, and Brazil.

As early as 1947, Julian and Judith began working on plays together, and this is the well-known and legitimate reason why Beck abandoned painting. In this regard, he said that he had decided to ‘dedicate [his] time to the more social art of theatre’. But the reality is more complex. The Siren and Muse of the Theatre captivated him forever; it is true. But Julian knew there was more to it than that. All art is lies, including poetry, with all its haughty verse. ‘Meretricious!’ I almost hear him cry. In the theatre, at least, there is a wider outlet. More engaging and universal. In any case and generally. ‘art is revolt. It is the revolt that fails’ (‘The Life of the Theatre’).

Abstract Expressionism was already in deep crisis in the late 1950s, a crisis of exhaustion, with new forces of young Turks on the attack: the exceptional Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and Cy Twombly, albeit still little known. But there were other reasons: Pop art (which Rauschenberg supported from the outset) was hammering furiously at the gates. In addition to Andy Warhol, Allan Kaprow and Claes Oldenburg were also Pop Artists, to name but two. At long last, the vilified painting on canvas was totally done for, destroyed in the fiercest and most scatological terrorist attack ever; the static nature of the canvas came to life in the happening.

Could Julian Beck simply stand by looking on, selling used books from the family library to buy canvases and paints? Thanks to Judith and him, the Living was already taking off. But I also believe that Julian Beck, the prophet, had also understood or guessed something else: calling art lies can be facile and immature. When art became an instrument of the Cold War, the question took a more worrying turn. But Julian, perhaps, had already suspected it when – I don’t remember precisely the year, but it was in the 1950s – he broke with Bill de Kooning, finding it objectionable that he accepted funding from the State Department, the representative of what he called the ‘Dominant Imperialist Democracy’. Poor Beck, perhaps he was already dead when Canadian art historian Serge Guibault’s seminal volume, entitled ‘How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom and the Cold War’, came out. The title has no need of comment; with great cunning the American Government, certainly no supporter of the arts of the time, thought it a wise move to use the inspired freedom of abstract art against baleful Socialist Realism. Julian Beck was suspicious of art and rejected it, but he couldn’t live without it. His work had always been one of startling joy: he knew only too well that creation is a human necessity, like food and a roof over our heads. Art is always a weapon, be it in the hands of repressors or the enlightened. Beck’s painting was an instrument of celebration and reflection at the same time. Art as a tool to build a grammar and from there to get to syntax. The sign is the code of language. A new language free of caution, not concerned with style or fitting in with fashion nor with being universally original. For this reason, the critic Philip Evans-Clark described him not only as a romantic but a ‘post modern’, even capable of making spirituality spectacular.

And not only in the theatre, we should add. And art, the object of so many suspicions, ‘is a help for evolution; this is its traditional function’ writes once again Julian Beck (this comment does not date from his youth, as it is from 1982). It is the sum, and only, rule of his whole life.

Gianfranco Mantegna, 1994